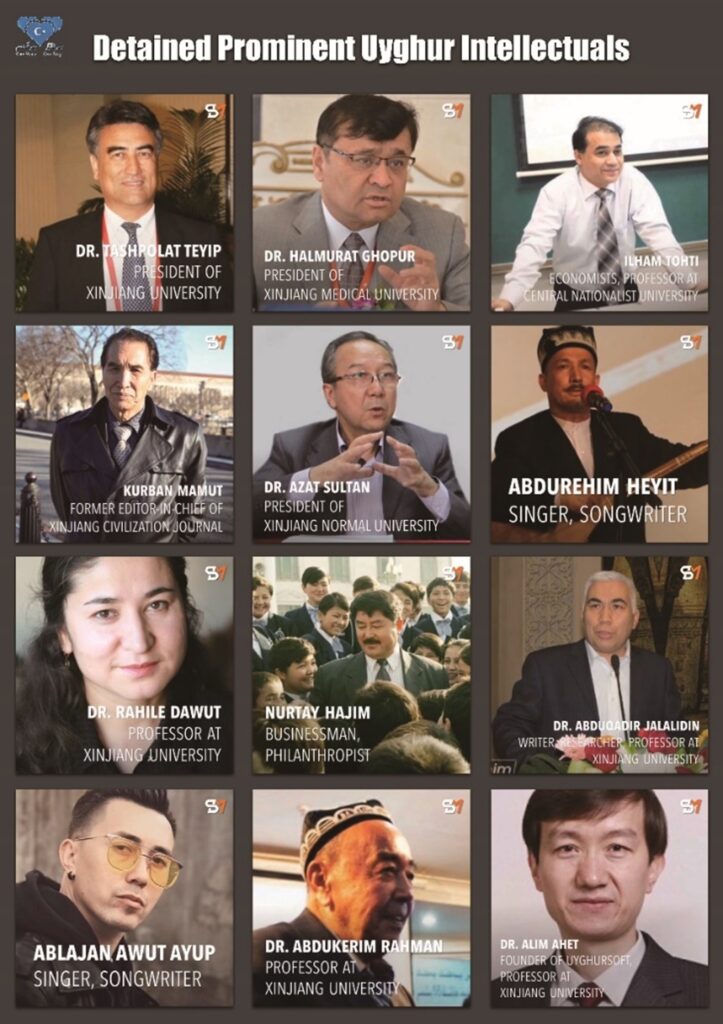

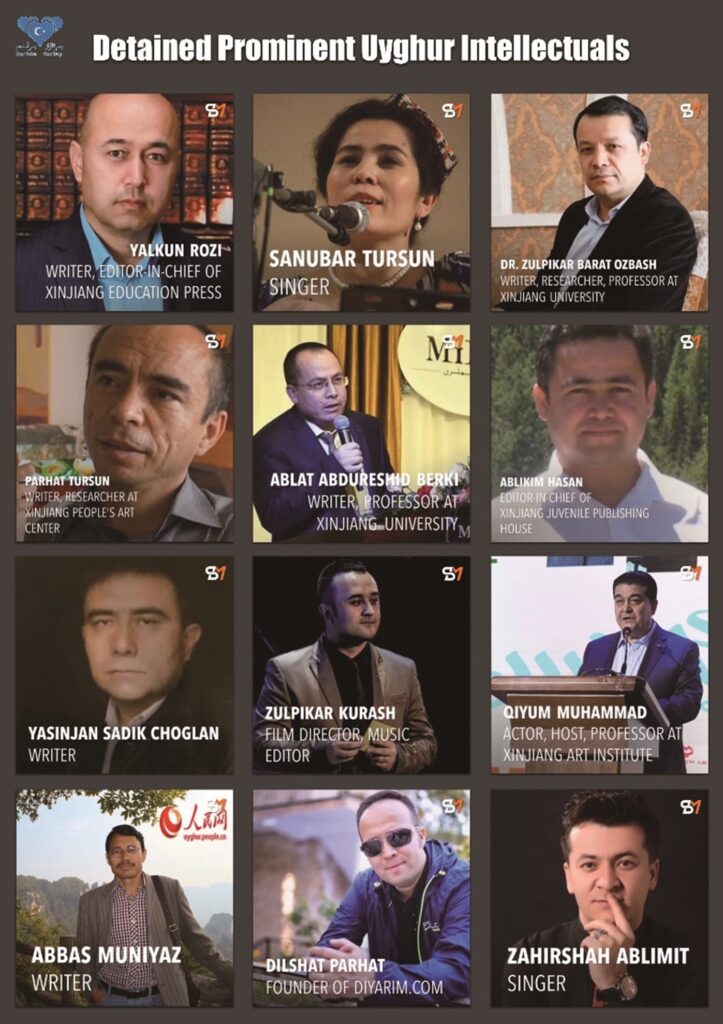

The Uyghur Human Rights Project, based in Washington DC, has documented the detainment and disappearance of 338 Uyghur intellectuals, artists, and academics as of April 2017. The number is thought to have increased in the 2 years since, as more and more people are sent to re-education camps. The absence of well-known thought leaders and influencers such as those pictured here has been deeply felt by all. Dr Rahila Dawut, the first Uyghur woman to receive her PhD in the Uyghur region, has been described as one of the most prominent figures in Uyghur anthropology, with colleagues and students across the world who have been shocked by her disappearance; she was seen as a bridge-builder between Western, Uyghur and Han-Chinese academia. Ilham Tohti was an economist living in Beijing who fully supported being part of a greater China, citing the negatives of becoming an independent state as China’s economy boomed. He believed implementing the constitutional rights given to autonomous regions would be the best way to create a better future. He was sentenced to life in prison for separatism. Ablajan Awut Ayup was described by the New York Times as the Uyghur Justin Bieber – he was a rags to riches story who had pop hits in Uyghur and Mandarin, while also using his popularity to promote children’s education. Most recently, rumours of Abdurehim Heyt’s death in prison – after serving two of his seven years – circulated like wildfire on social media, which prompted the Turkish Foreign Ministry to release its strongest statement against China’s treatment of Uyghurs. Within a few days, a video was released showing Heyt against a washed out grey background, stating the date of recording and the fact that he was healthy. This sparked the #MenmuUyghur or #MeTooUyghur hashtag, which urged the Chinese government to send proof-of-life videos of everyone’s family members who had been detained.

The arrest of Uyghur intelligentsia is not a new phenomenon. Waves of arrests and executions since occupation by the Chinese Communist Party have occurred under different guises at the turn of every other decade; a crackdown on Uyghur “nationalists” (or “Chinese chauvinists”) in the 1950s, on revisionists, bourgeois or those with foreign (capitalist) ties in the 60s and 70s, on separatists in the 80s and 90, on separatists or terrorists after 9/11, and now, “two-faced” persons (often with separatist or terrorist ties). The victims have always been the same – Uyghur intellectuals who could promote progress in their society, which the CCP saw as a threat.

There is a cognitive dissonance felt as China touts its programs to help “minorities” achieve growth in the educational and cultural sectors, while arresting those who actually do well; added to the general workplace discrimination which prevents Uyghurs from applying to some places, or being promoted too highly in others, Uyghurs are deeply discouraged from achieving anything too great or acting with true intellectual freedom. Once deprived of representation in the public sphere, the general populace become entirely dependent on the CCP for all matters in life – opinion, religion, culture. In the diaspora, those with the capacity feel obliged to divide intellectual effort between a career they are passionate about, and advocacy, activism, and the struggle to keep their family and friends alive.

In Henryk Szadziewski’s essay “Disappeared Forever? The persecution of Uyghur intellectuals” he draws a parallel to his native Poland in World War 2:

In 1939, the Nazis implemented ‘Intelligenzaktion,’ a policy that singled out Poland’s intelligentsia. Selected people were targeted, disappeared and murdered. The aim was not only to “cleanse” the newly conquered territory, but also to wipe out any source of opposition to Nazi rule. Professor Jan Pakulski writes that these “eliticides” resulted in the “formation of a politically dependent and socially deracinated ‘quasi-elite’ with limited capacity for governing.”

Prominent figures from all aspects of life have been affected by the sweep on Uyghur intelligentsia, from medical practitioners to poets, singers and comedians to academic professors, from the education sector to webmasters and publishing houses. Bookstores have been shuttered down as books in the Uyghur language have been confiscated and destroyed. Publishers that had once published state-approved educational textbooks have had their plugs pulled. This follows China’s nation-wide ban on VPNs and access to academia deemed inappropriate by the Chinese government, which foreign publishers such as Springer Nature and Francis & Taylor have complied with, despite international outrage on the curbs of intellectual freedom. The crackdown on Uyghur scholarly society is a dangerous and concerning phenomenon. The impact will be generational, as decades-worth of painstakingly collected research material is deleted or destroyed.

The effects on the arts and culture is also significant; Sanubar Tursun, an esteemed folk musician who was supposed to perform in several French cities in February 2019, has been missing for months now. She carries with her knowledge of Uyghur musical traditions that may be lost forever, as Chinese government institutions rewrite and standardize Uyghur folk music and its history to fit their own narrative.

The last poem written by famous poet Chimengul Awut before disappearing into a camp was a short message to her son on her social media: “Jan qozam / Yighlimighin / Sen uchun yighlar jahan” – “My dear lamb / Do not cry / The world will cry for you”.

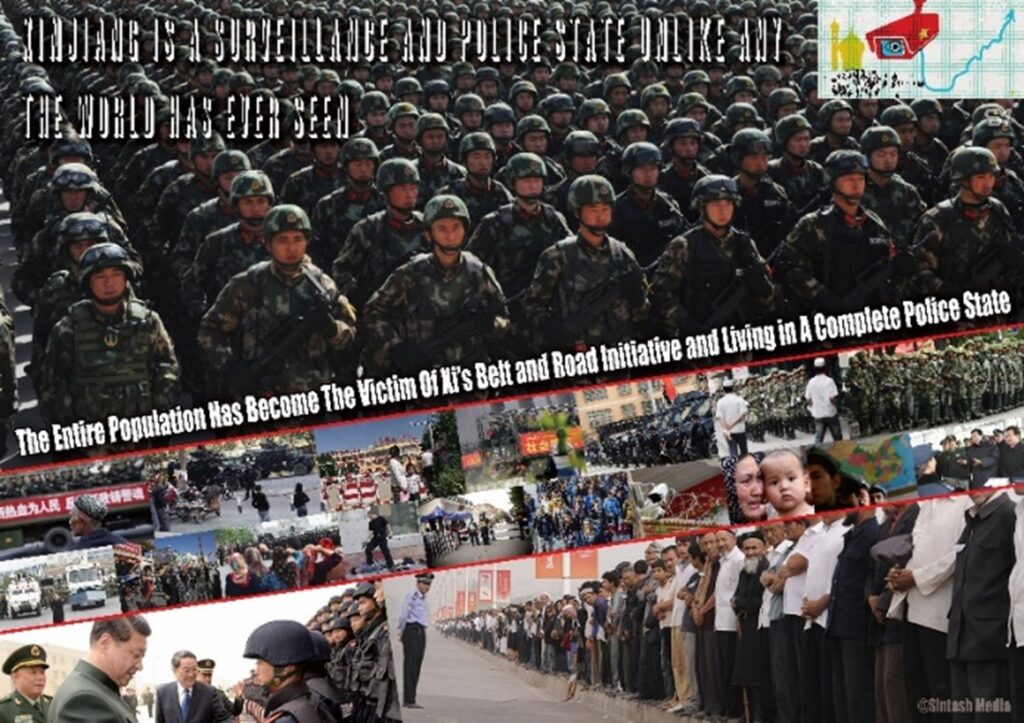

2. Total Police State

The Uyghur region has been described as a “police state” by a number of academics and major news outlets. This is because Uyghurs are subjected to:

- Enforced collection of all biometric data, including DNA, voice samples and gait

- Compulsory spyware apps and regular checks on all electronic devices

- Digitally coded ID cards to track movement

- Increased number of CCTV cameras around Uyghur-populated areas

- Police blockhouses every hundred or so metres

- “Becoming Family” extended homestays by government workers

- Security checkpoints on roads and in shopping centres, banks, etc

These security checkpoints have two lanes: one for Han and obvious foreigners, who are quickly waved through, and another for anyone who looks Uyghur, who are searched multiple times a day.

For many years now, but starting in earnest in 2016, there have been reports of Uyghurs being sent to “re-education” for an indefinite amount of time. Detainees are subject to political indoctrination, forced denunciation of religion and identity, highly unsanitary conditions, abuse and torture. There are at least 73 confirmed re-education centres holding an estimated 1 million people, mostly Uyghur but also including Kazakh, Kyrgyz, and other ethnic minorities, although some reports estimate over 180 centres have been built, some of which are repurposed middle schools. One can be sent to “re-education” for doing things like quitting smoking or wanting to travel abroad. Detainees are denied due process or access to legal representation.

After initially denying the existence of these camps, China reiterated their stance and claimed they were “vocational training centres”. However, spending on vocational training decreased by 7% from 2016 to 2017, while security spending in the region rose by US$2.9 billion (213%). Spending on domestic security in the region was three times the national average that year and has not slowed in the last year.

It is believed that one of the main reasons why the Uyghur region has been placed under such heavy securitization is due to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Going into effect in 2013, the BRI aims to link Beijing with some 70 countries around the world via railroads, gas pipelines, shipping lanes, and other infrastructure projects.

- https://www.economist.com/briefing/2018/05/31/china-has-turned-xinjiang-into-a-police-state-like-no-otherhttps://www.hrw.org/report/2018/09/09/eradicating-ideological-viruses/chinas-campaign-repression-against-xinjiangs#https://www.afp.com/en/inside-chinas-internment-camps-tear-gas-tasers-and-textbookshttps://foreignpolicy.com/2018/09/13/48-ways-to-get-sent-to-a-chinese-concentration-camp/https://chinachannel.org/2018/11/23/checkpoint-nation/https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/03/opinion/sunday/china-surveillance-state-uighurs.htmlhttps://jamestown.org/program/xinjiangs-re-education-and-securitization-campaign-evidence-from-domestic-security-budgets/https://www.businessinsider.com/map-explains-china-crackdown-on-uighur-muslims-in-xinjiang-2019-2

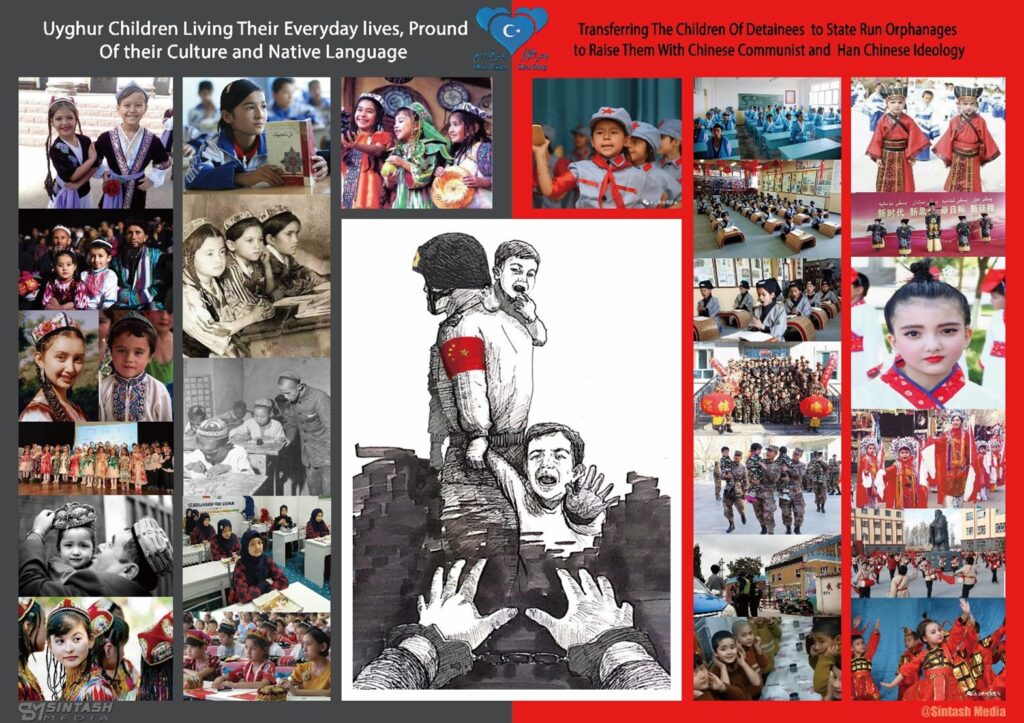

What are the effects of arbitrarily detaining over one million adults? Thousands of children are left homeless and sent to state-run orphanages. Sometimes, even those with relatives willing to take care of them are instead sent to the orphanages. Despite being “orphans”, many of these children’s parents are still alive.

Propaganda images and videos of children learning about Han customs, dressing in Han cultural clothing, and singing praises of Xi Jinping and the Communist Party have circled the internet for months – distressingly, some parents living abroad have spotted the children they had been cut off from in such videos. Separating children from their families and teaching only the culture of China’s majority reflects the practices of the re-education camps, which force adults to denounce their Uyghur identity and any religious faith they may have.

With the state-run orphanages, an entire generation of Uyghur children have been removed from their cultural and religious roots, in what could be one of the most devastating assimilation policies China has implemented. The negative effects of family separation and forced education can still be seen in populations such as the Stolen Generation of Australia, or the Native American children sent to assimilation “boarding schools” in North America.

The orphanages follow on from assimilation policies of the last decade, for example, the banning of many common Islamic names, which has made many parents change their children’s names. Those who kept names such as “Muhammad” risked not being allowed to enrol in school. The education system also saw the introduction of “bilingual education” which effectively made all schools teach in Mandarin, while the Uyghur language was relegated to an optional second language subject.

Children sent to mainland where it will be near impossible to reunite with family.

4. Forced Marriage

Marriages between Uyghur and Han have always been extremely rare (only 0.2% in 2010 according to one study based on Chinese census data)4, yet since the beginning of the camps, there seems to have been an increase in news of interethnic marriages. In a time where over a million Uyghur people are detained, where some regions have specifically targeted all Uyghur men born in the 1980s onwards5,6, where there has been an increase in the racial profiling and mistreatment of Uyghurs compared to Han, it is difficult to say that Uyghur-Han relations in general have been any good, let alone romantic relationships. Rumours from within the region whisper of Uyghur women who are unable to refuse Han wedding proposals, or else risk the detainment of her entire family. All of this, together with China’s previous track records of human rights abuses, highly intrusive assimilation policies, the “shortage of women” in mainland China, and the complete lack of response from the international community in retribution to their actions, it seems likely that Han locals and officials are abusing their power against at-risk Uyghur women who are unable to challenge authority. The silence from the Uyghur brides are particularly deafening.

- [1] https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/18335330.2018.1475746?af=R

- [2] https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/05/13/china-visiting-officials-occupy-homes-muslim-region

- [3] https://journalofchinesesociology.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40711-017-0059-0

- [4] https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/1980-03222018155500.html

- [5] https://livingotherwise.com/2017/12/05/love-fear-among-rural-uyghur-youth-peoples-war/

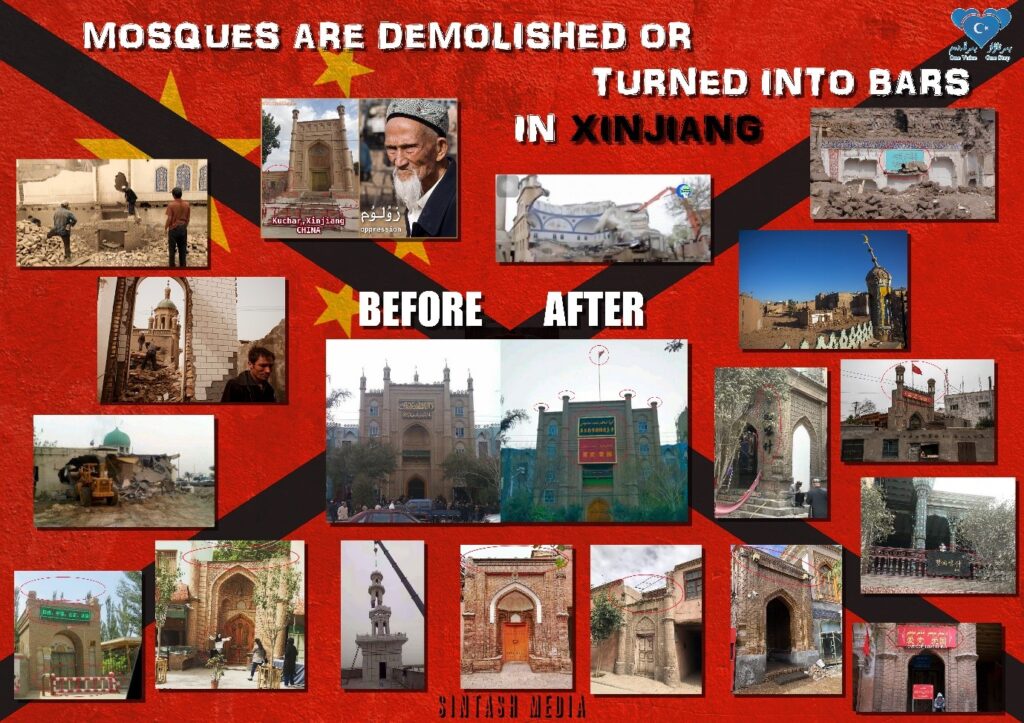

5. Demolished Mosques

Once teeming with life, particularly during religious celebrations such as Eid, mosques are now largely deserted as religious piety is met with extreme suspicion. At first, children and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) employees were banned from mosques. Later, prayers and sermons were changed to fit a Sinicised version of Islam that praised Xi Jinping and the CCP instead of Allah (SWT). Once the crackdowns began in earnest, all religious items such as prayer mats and Qur’ans were confiscated from homes, and those found with such contraband were sentenced to years in prison. So were people who taught Islam to children – some state that children were encouraged to report to their teachers at school if any sort of religious education took place at home. Once the re-education camps were introduced, some of the first groups of people detained were religious people, including imams that had been trained by the Chinese government. Now, famous mosques have become museums for tourists to take photos of, with just a handful of representative practitioners in attendance. Those mosques still standing are more populated with CCTV cameras than people, Party propaganda than religious art, Chinese flags than moon and crescent symbols, which once topped the minarets, and are surrounded by barbed wire fences. Other mosques have been demolished or revamped to serve as bars or hookah lounges. RFA estimates that by 2016, at least 5,000 mosques had been demolished. This has begun to spread to mainland China, where mosques in Hui communities of Ningxia are being demolished. Many Churches have also been demolished as the crackdown on religion expands.

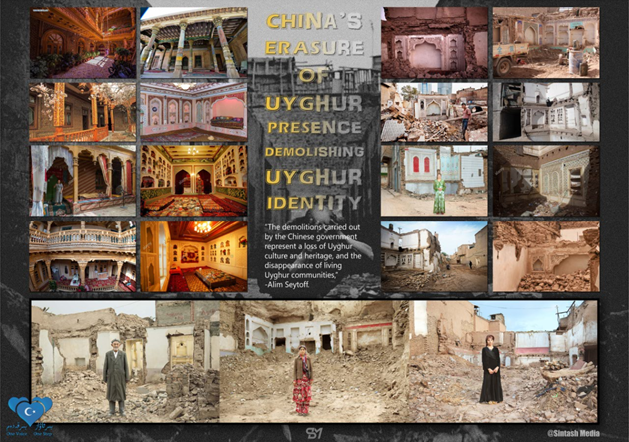

6. Kashgar Demolition

Kashgar is one of the oldest cities of Central Asia, and the capital of many Uyghur states in the past, most notably the Karakhanid Khanate, the Chagatai Khanate, the Emirate of Yaqup Beg, and the First Eastern Turkistan Republic. It is considered by the Uyghur people as the cradle of their post-Buddhist history and civilization.

Starting in 2009, the government began to destroy the old city piece by piece – purportedly to “modernise” Kashgar and create better and safer infrastructure in case of an earthquake. Uyghur residents were displaced into suburban housing projects while the city centres were transformed into a façade of what it once was, described by returning visitors as an ethnic “theme park” where tourists could ogle at Kashgar’s New Old Town and visit Uyghur homes.

Some of these photos of the destruction is from photographer Édith Roux’s series “The Dispossessed” (Kashgar, 2010-2011). In an accompanying article in The Funambulist, P Reyhan writes:

“…spatiality is also an important element of identity. Studies in social geography show the importance of notions of public space, living space (practical and imaginary), and territoriality for a human being’s formation of self and social and spatial relationships. The geographer Guy Di Méo explains more precisely the role of spatiality and geographical places in the lives of individuals… spatial contexts (spaces of living, custom, or everyday actions) … become extensions of one’s own body and inscribe themselves subsequently into one’s system of identity… It is socially signified, symbolically qualified by relations, by social positions and stakes. The destruction of a place is also the destruction of its history, its past, and its memory in order to build a new identity — in this case, one appropriately ‘Chinese.’”

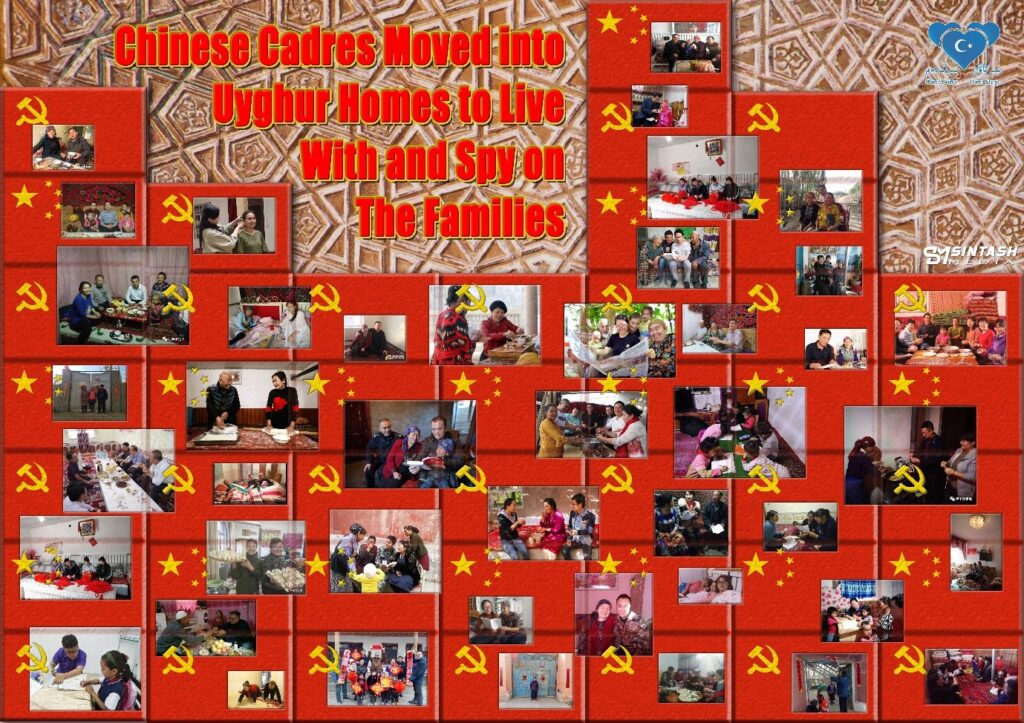

Uyghur families have been assigned Han “relatives” to stay in their homes and record their activities under the guise of helping and educating locals – over a million Han government workers were sent to Uyghur homes to share beds, eat pork, and praise Xi Jinping. In some regions, Uyghur households are divided into groups to spy on each other. Those deemed suspicious are sent to re-education camps.

According to Human Rights Watch, reports began in 2014, when 200,000 cadres from government agencies, state-owned enterprises, and public institutions were required to regularly visit and surveil people. Authorities stated that this initiative, known as “fanghuiju” – an acronym for “Visit the People, Benefit the People, and Get Together the Hearts of the People” was necessary for stability. In 2016, the “Becoming Family” campaign began, where at least 110,000 officials visited the largely Turkic Muslim population in southern Xinjiang for five days every two months in order to “foster ethnic harmony.” By 2017, this number grew to more than 1.1 million cadres, who spent a week living in mostly Uyghur homes. Come 2018, cadres were spending up to one month in these homes. There is no evidence to suggest families can refuse visits or homestays.

During these visits, families are required to provide officials with information about their lives, political views, and religion, and are subjected to political indoctrination. “Problems” ranging from levels of cleanliness, alcoholism, or praying at home, can lead a cadre to “rectify” the situation. This is a chilling intrusion into the private lives of regular citizens, and the result has been a growing number of people sent to re-education camps.